Excuse me while I teleport back to New York of April 2020, into this surreal mix of pandemic grief and lockdown amid a gently emergent spring, pink blossoms and fragrant air. My transport is experiencing delay. I’m still walking the streets of war-ravaged London, Christmas 1947, where the foundations of bombed-out buildings, under a light frosting of snow, suggest the outlines of ancient Roman ruins—the key to a puzzling series of murders.

Give me another sec. Almost here, still a bit there. Let me knock back the last tumbler of gin and crush out my red lipstick-stained cigarette. Unfiltered.

Give me another sec. Almost here, still a bit there. Let me knock back the last tumbler of gin and crush out my red lipstick-stained cigarette. Unfiltered.

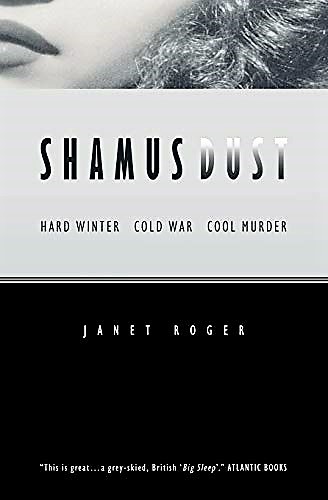

Janet Roger is to blame. Her debut novel, Shamus Dust, pulled me in and keeps running like a 40s black-and-white film noir on the brain.

I’m no fan of categories and hesitate to apply a label or “genre” to this work of art. Hard-boiled, gritty, and atmospheric, yes, but also poetic and literary. Roger confesses a Raymond Chandler influence, and the similarities are evident, but her prose isn’t as spare and tough when she’s in the mood to embellish. There are moments when this book is purely about the writing. While some reviewers say that it takes them out of the story, this lover of language found it right up her alley. More on that later.

The story is told from the point of view of an American private investigator called Newman, or Mr. Newman—a man who possibly lacks a first name. An insightful interpreter of human frailties and dark motives, Newman moves in a world of distinctive characters from every stratum of society. By the end of the book, the upper crust is looking seedier and far less heroic than the inhabitants of London’s underbelly. Roger has created a large cast of characters, gradually dropping tidbits to reveal their back stories and relationships. To mention a few: Councilman, archaeologist, entrepreneur, architect, lawyer, medical examiner, police commissioner, detective inspector, nurse, barber, haberdasher, pimp/blackmailer, various prostitutes, and a homeless shell-shocked WWII vet. Add several murders, a rotating field of suspects, a complex web of clues, and you’ve got one hell of a novel, with an ending you won’t see coming.

Shamus Dust is not a beach read or superficial entertainment to pick up when you’re mildly distracted. You’ll need to take this one slowly to savor the language, its sophistication, wit, irony, unique metaphors, and turns of phrase. You’ll need time to ponder the complexity of the plot. The author honors the reader’s intelligence, never overstates, poses one intriguing puzzle after another. She follows Newman through London without revealing what he’s up to in a scene until, several pages on, the reader is allowed to discover the meaning of the interaction. There are many of these “ah-ha” moments, opportunities to marvel at the cleverly interlacing intricacies.

Shamus Dust is not a beach read or superficial entertainment to pick up when you’re mildly distracted. You’ll need to take this one slowly to savor the language, its sophistication, wit, irony, unique metaphors, and turns of phrase. You’ll need time to ponder the complexity of the plot. The author honors the reader’s intelligence, never overstates, poses one intriguing puzzle after another. She follows Newman through London without revealing what he’s up to in a scene until, several pages on, the reader is allowed to discover the meaning of the interaction. There are many of these “ah-ha” moments, opportunities to marvel at the cleverly interlacing intricacies.

The writing style. The word choices. Here are just a few.

Physical descriptions that instantly evoke an image:

“The kind of room where you’re meant to sit at night in a cravat and a quilted robe reading Kipling by firelight until the Madeira runs out.”

A woman with a “mouth that made the fall of dark-red hair look incidental.”

“Littomy’s nose was built for a profile on old coins.”

A man’s “hair shone in flat stripes across the dome of his head, where you could count them if conversation ran thin.”

At a party attended by the one percent, a young scion is “wearing black-tie as if he’d been weaned in it.”

Chandleresque:

A volatile thug looks like “he could hurt a man and enjoy the work.”

Witty dialogue:

The butler to a sloshed hostess asks Newman what he would like to drink. He replies, “Not a thing. Mrs. Willard will be taking cocktails for both of us.”

And how are these lines for poetry?:

“Night was crawling in a deep, wet hole.”

“She put a hand flat against my chest and her gaze dipped back in an ocean, then surfaced again, dripping its dark purple lights.”

“He looked wild-eyed around a room so hushed you could hear him blink away the tears.”

The book opens with one of my favorite, longer passages. Newman says he has never had trouble falling asleep and “sleeping like the dead” until now:

“Lately, I’d lost the gift. As simple as that. Had reacquainted with nights when sleep stands in shrouds and shifts its weight in corner shadows, unreachable. You hear the rustle of its skirts, wait long hours on the small, brittle rumors of first light, and know that when finally they arrive they will be the sounds that fluting angels make. It was five-thirty, the ragged end of a white night, desolate as a platform before dawn when the milk train clatters through and a guard tolls the names of places you never were or ever hope to be. I was waiting on the fluting angels when the telephone rang.”

Wow. Any insomniac (namely, me) can relate.

Now, don’t you want to read something like this? I may teleport back there now.