For this installment of Fiction Favorites and Awesome Authors, I’m delighted to welcome author Richie Narvaez to VBlog for a conversation about his recently released debut novel.

The title alone piques your interest, doesn’t it? And how about that cover art by JT Lindroos? Very eye catching. But more important: This is a debut novel not to miss.

If you like crime fiction and want something different and unique, this is for you, especially if you live, or have ever lived, in New York City. To avoid spoilers, I won’t give away any more of the plot than what’s in the publisher’s blurb:

Murder is trending. Hipsters are getting slashed to pieces in the hippest neighborhood in New York City: Williamsburg, Brooklyn. While Detectives Petrosino and Hadid hound local gangbangers, slacker reporter Tony Moran and his ex-girlfriend Magaly Fernandez get caught up in a missing person’s case—one that might just get them hacked to death.

Filled with a cast of colorful characters and told with sardonic wit, this fast-moving, intricately plotted novel plays out against a backdrop of rapid gentrification, skyrocketing rents, and class tension. New Yorkers and anyone fascinated with the city will love the story’s details, written like only a true native could. Entertaining to the last, this rollicking debut is sure to make Richie Narvaez a rising star on the mystery scene.

I was fortunate to attend the launch party for Hipster at the Mysterious Bookshop in Manhattan, where the author treated us to a reading of the first few pages. His lively and vivid writing was made even more so by his spot-on delivery and timing. Let’s hope that an audio book narrated by Narvaez himself is in the future.

The novel features a large cast of characters, people from all walks of life and many ethnicities. From a lesser author this might pose a problem, but Narvaez has a knack for making his characters memorable. They come alive on the page through quirky physical traits, dialogue and actions, details about where they live, what they eat, what stores they patronize, and the pets they own. In one scene, for example, a seven-month pregnant thirtysomething yuppie named Erin and her husband Steven (for whom she has endless cutesy nicknames such as “Stevely,” “McSteven,” and “Steve-o-rini”), dine at a new Burundian restaurant in Williamsburg and, slightly nauseated from the Burundian bananas and beans, return to their condo in an upscale, glittering glass tower with river view, where Erin smartly thanks her Mexican doorman with a “Gracias,” confident in the perfection of her Spanish accent because she actually once had a Mexican friend in Texas who complimented her on it. I was laughing.

As you may guess from the book blurb, there are, indeed, machete slashings in Hipster, but if excessive gore gives you nightmares (as it does for me), rest assured that the bloody details are kept to a relaxing minimum, leaving the reader to use his or her imagination, as desired. In the context of the murder mystery and police investigation, social commentary about gentrification and ethnic tensions is expertly woven into the plot in a non-preachy, entertaining way. The author gives us, for example, the dying thoughts of some of the victims, which invariably include emotion-laden regrets about the imagined fate of their apartments after they die. It’s hilarious, but at the same time, a statement about the universal preoccupation of New Yorkers with housing and real estate.

And now, I’m pleased to say that the author has graciously agreed to answer some of my burning questions.

Welcome to VBlog, Richie. I thoroughly enjoyed Hipster Death Rattle. Social commentary figures prominently in your novel, enhancing, never detracting from, the story line and characters. What led you to incorporate this theme into a murder mystery as opposed to, say, a literary or mainstream novel, and what do you see as the advantages of this format?

Ah, well, I did originally try to write Hipster as a mainstream book, but it was too close to me and I stumbled. I couldn’t get past my own bitterness about gentrification in Williamsburg, and all the characters were just talking points, not people. I needed a plot to anchor my pain and my ideas.

And that’s the thing about genre writing isn’t it, the thing that drives literary or mainstream snobs mad: it’s got plot! I could’ve done this as a horror or sci fi novel, but crime fiction is the most grounded of the so-called genres, and I wanted this story to have literal resonance, not metaphorical. And crime fiction is a very flexible format—flexible as a dancer! You ignite the story with the mystery, and the process of its being solved allows the protagonists and the reader to encounter people and points of view.

Of course some readers would prefer to have their corpses served without a side of social commentary, so I may lose those readers. But many of the greats—Christie, Chandler, Highsmith, Paretsky—have social commentary in their works. Crime fiction is actually a perfect vehicle for social commentary.

I knew there was a reason I keep dancing—to make my crime fiction better! As for the flexibility of the genre…maybe this book was therapy or vicarious payback for you? (“Lolz,” as your character Gabrielle likes to say.) “No one there is who loves a hipster,” whispers the murderer as he comes upon his next victim. How much of this is personal for you, based on your experience, witnessing the gradual transformation of the neighborhood of your youth?

It’s all very personal. I was born in Greenpoint Hospital and raised in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. I went away for college, but then returned to witness the rise of gentrification. Slowly, gradually, I saw people displaced, many of my friends and relatives, and I saw the disrespect and erasure of the culture of the people who had lived there for so long.

To be clear, gentrification is not a natural process. Yes, neighborhoods change hands all the time, but gentrification is different, it’s insidiously manufactured, a combination of real estate developer and governmental cunning, urban renewal for profit, not for people.

I’m not sure how much payback there is in writing the book. The Powers that Be would likely not take notice, and they will likely never be punished for their greed. But, therapy, yes, a little. Although the pain does not go away completely. It just feels better for a little while.

Carpe diem, Richie. My Latin is a little rusty, but…

Hah! Habeas corpus and obiter dictum!

Touché! Yes, we lawyers tend to sprinkle in the Latin and forget that it isn’t English. But I did learn some new non-legal Latin from your book. I like the way you worked it into the dialogue between Chino and his former college professor and bad guy, Litvinchouk. We understand most of it in context, and it adds a lot of humor to their relationship. How did this idea come about?

The Latin thing came ab initio from the fact that the person I partially based the character of Chino on actually did minor in Latin in college. So at first it was just a neat character detail, and it allowed me to spend hours learning some very basic Latin myself. But then I realized it added some irony. People hate hipsters for being snobby. Yet, here is a main character who holds on to and cusses in a dead tongue, a language darling to the elite and the intellectual. Also, Chino is a Latino who can speak Latin but not Spanish, underlining his separation from his own culture, Othering him to underscore his status as another kind of hipster himself.

What are your tips for writers who want to incorporate irony and humor into their writing? Or does this just come naturally to you and woe to us?

I have to say the humor seems to come fairly naturally for me. A genetic quirk. Or the legacy of a sensitive childhood. Although, I have to say, in the first draft of Hipster there was no humor. I was trying to be a serious crime writer and write seriously about a serious subject. But I realized I wasn’t very satisfied with that, and it kind of bored me. So I went back and added in the funny.

Now, it’s difficult to tell someone how to be funny and ironic. Not taking yourself too seriously is key. And I will say the chief tool to use is surprise. Humor and irony come out of the unexpected. So, as you’re writing along, stop and think about what everyone expects will happen or be said next, and then do the opposite or at least sideways, something silly and/or something that resonates with the theme of what you’re trying to say. In any case, don’t give the readers what they expect.

Good advice for writers, but I won’t allow you to thwart something I’m expecting from you: more great writing. What’s next? What’s on your computer screen these days?

Littering my desktop are several short stories in various stages as well as a novel, but that seems to be a permanent state of affairs for me. At the moment I’ve got a YA novel making the publisher rounds. And there’s a second book of short stories, to follow Roachkiller and Other Stories, I hope to have out next year.

Best of luck on all these endeavors, Richie. I look forward to reading your next book.

Dear Readers,

You can get Hipster Death Rattle from Down and Out Books (see also links to booksellers on the Down and Out Books site), and at the Mysterious Bookshop.

After reading Hipster, if you’re looking for more good summer reading, I’ve built up quite an archive of book reviews and author Q & As. Click the VBlog tab, and then, on the sidebar, “Fiction Favorites and Awesome Authors” or “Legal Eagles” (my series on attorneys writing fiction). You will find articles on books by all of these amazing authors and more: Kevin Egan, Nancy Bilyeau, Manuel Ramos, Allison Leotta, Adam Mitzner, Kate Robinson, David Hicks, Helen Simonson, Eowyn Ivey, William Burton McCormick, and Allen Eskens.

Happy reading!

One of my readers gave me

One of my readers gave me  to the theme. In the opening piece, “Ordinary Life: A Love Story,” a woman of 79 takes a week-long timeout from her husband to reflect on her life. The memories and images of people, possessions, and family milestones tumble out in a free flow of association. At this stage of her life, she wonders where the time went and what’s next. “How could she have known that ordinary life would have such allure later on?”

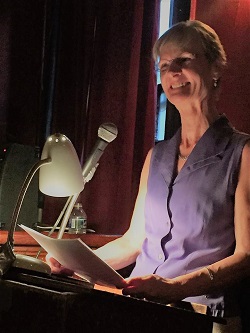

to the theme. In the opening piece, “Ordinary Life: A Love Story,” a woman of 79 takes a week-long timeout from her husband to reflect on her life. The memories and images of people, possessions, and family milestones tumble out in a free flow of association. At this stage of her life, she wonders where the time went and what’s next. “How could she have known that ordinary life would have such allure later on?” speaking of short stories, here I am at the iconic

speaking of short stories, here I am at the iconic

For more stories, check out my collection

For more stories, check out my collection

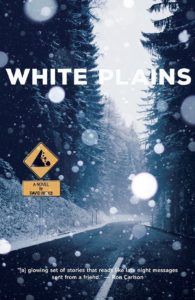

I’m pleased to welcome David Hicks to VBlog for this installment of Fiction Favorites & Awesome Authors. His debut novel

I’m pleased to welcome David Hicks to VBlog for this installment of Fiction Favorites & Awesome Authors. His debut novel

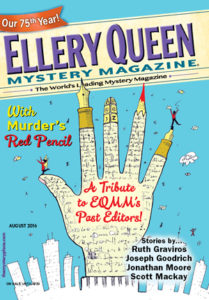

I was first introduced to Bill McCormick’s fiction when we shared the pages of

I was first introduced to Bill McCormick’s fiction when we shared the pages of  McCormick’s short story “

McCormick’s short story “ As the novel progresses, Wiktor finds more distance from his aristocratic roots, loses his prejudices as he forms personal relationships with Latvians in his regiment, and falls in love with a Latvian woman, Kaiva, who believes in communism. The novel contains impressive insights into relationships that are fraught with conflicting societal and political tensions. One of my favorite scenes is the dinner party where Wiktor introduces his fiancée Kaiva to the family. All is going reasonably well, the family almost accepts her, when a family member mentions that he has petitioned the League of Nations for the return of the family’s land, “illegally seized” by the Latvian government. Idealistic Kaiva innocently professes puzzlement: “Your life seems more than comfortable. Why do you need more?” She observes that their land, which once supported a single family, now supports several Latvian families: “It’s simply a better use of the land.” Who could argue with that? Well, the insult is ultimately tempered somewhat when Kaiva is asked to consider how she felt when she was thrown from her home and became a refugee, causing her to admit that the loss of home is traumatic, no matter what the reason.

As the novel progresses, Wiktor finds more distance from his aristocratic roots, loses his prejudices as he forms personal relationships with Latvians in his regiment, and falls in love with a Latvian woman, Kaiva, who believes in communism. The novel contains impressive insights into relationships that are fraught with conflicting societal and political tensions. One of my favorite scenes is the dinner party where Wiktor introduces his fiancée Kaiva to the family. All is going reasonably well, the family almost accepts her, when a family member mentions that he has petitioned the League of Nations for the return of the family’s land, “illegally seized” by the Latvian government. Idealistic Kaiva innocently professes puzzlement: “Your life seems more than comfortable. Why do you need more?” She observes that their land, which once supported a single family, now supports several Latvian families: “It’s simply a better use of the land.” Who could argue with that? Well, the insult is ultimately tempered somewhat when Kaiva is asked to consider how she felt when she was thrown from her home and became a refugee, causing her to admit that the loss of home is traumatic, no matter what the reason.

Most surprising is the intense suspense created by the comings and goings of the snow maiden. She is the personification of a beautiful but ever-changing wilderness, and like the main characters in the novel, we want her to remain with us while constantly fearing the moment when she will be gone.

Most surprising is the intense suspense created by the comings and goings of the snow maiden. She is the personification of a beautiful but ever-changing wilderness, and like the main characters in the novel, we want her to remain with us while constantly fearing the moment when she will be gone. As Forrester’s party trudges through ice canyons of terrifying beauty, encountering setbacks, privation, sickness, and near starvation, the lines increasingly blur between man and beast, perception and reality, the corporeal and the mystical. These slender divisions: are they magic or the products of hallucination, brought on by hunger, exposure, and suggestion?

As Forrester’s party trudges through ice canyons of terrifying beauty, encountering setbacks, privation, sickness, and near starvation, the lines increasingly blur between man and beast, perception and reality, the corporeal and the mystical. These slender divisions: are they magic or the products of hallucination, brought on by hunger, exposure, and suggestion? has a lot of darkness and brutality. If I can see all of that clearly, how can I still be so attached to it and be sure I don’t want to live anywhere else? But through the writing process, I’ve come to suspect that is the nature of love. In order to love someone or something with honesty, beyond just the postcard image, maybe I have to know all its flaws and terrors. So I feel like I’m making peace with some element of that. At the same time, Alaska’s past and present is complex, like any place I suppose, so I don’t feel as if I’ve got it all neatly buttoned up. I’ve still got some questions to work with as a writer.

has a lot of darkness and brutality. If I can see all of that clearly, how can I still be so attached to it and be sure I don’t want to live anywhere else? But through the writing process, I’ve come to suspect that is the nature of love. In order to love someone or something with honesty, beyond just the postcard image, maybe I have to know all its flaws and terrors. So I feel like I’m making peace with some element of that. At the same time, Alaska’s past and present is complex, like any place I suppose, so I don’t feel as if I’ve got it all neatly buttoned up. I’ve still got some questions to work with as a writer. First off, thank you so much for that. One of my main aspirations with the novel was to allow readers to experience the adventure for themselves as much as possible, so I’m so thrilled at your response. And absolutely, even after spending my entire life in Alaska, I continue to be overwhelmed and in awe of the wilderness. This touches on the previous question, about my conflicting emotions about Alaska, because it can be simultaneously magnificent and terrifying. I’ve had the more stereotypical encounters—being charged by a grizzly bear, watching the northern lights on a winter night, sleeping in a remote cabin when it’s 40 below zero outside. But more often the moments are unexpected, like when I’m picking wild blueberries on a mountainside and I stop to stretch my back and realize that as far as I can see in any direction there is not another human being, only mountains and tundra and rivers. It’s a bracing, humbling sensation.

First off, thank you so much for that. One of my main aspirations with the novel was to allow readers to experience the adventure for themselves as much as possible, so I’m so thrilled at your response. And absolutely, even after spending my entire life in Alaska, I continue to be overwhelmed and in awe of the wilderness. This touches on the previous question, about my conflicting emotions about Alaska, because it can be simultaneously magnificent and terrifying. I’ve had the more stereotypical encounters—being charged by a grizzly bear, watching the northern lights on a winter night, sleeping in a remote cabin when it’s 40 below zero outside. But more often the moments are unexpected, like when I’m picking wild blueberries on a mountainside and I stop to stretch my back and realize that as far as I can see in any direction there is not another human being, only mountains and tundra and rivers. It’s a bracing, humbling sensation.

“Kirkus recently reviewed three legal thrillers that focus on resourceful attorneys pursuing justice. In V.S. Kemanis’

“Kirkus recently reviewed three legal thrillers that focus on resourceful attorneys pursuing justice. In V.S. Kemanis’  In The Mulvaneys, near the end, a 210-word sentence describes a family softball game, with vivid depictions of five characters, the pitcher, batter, umpire, first baseman and third baseman. I’d venture to guess that the novel contains hundreds of sentences this length or longer, jamming the many page-length paragraphs that rush headlong toward elusive end points. I didn’t stop to count the words. I was too busy reading, too enthralled. After closing the last page and drying my tears, I took a moment to mourn my personal loss of the Mulvaneys, as my real-life living room slowly came into focus—a world without them. After getting through all of that, I remembered the sentence about the softball game, went back, and counted the words.

In The Mulvaneys, near the end, a 210-word sentence describes a family softball game, with vivid depictions of five characters, the pitcher, batter, umpire, first baseman and third baseman. I’d venture to guess that the novel contains hundreds of sentences this length or longer, jamming the many page-length paragraphs that rush headlong toward elusive end points. I didn’t stop to count the words. I was too busy reading, too enthralled. After closing the last page and drying my tears, I took a moment to mourn my personal loss of the Mulvaneys, as my real-life living room slowly came into focus—a world without them. After getting through all of that, I remembered the sentence about the softball game, went back, and counted the words. On to TransAtlantic by Colum McCann. The construct of this novel is unique. McCann takes three fact-based story lines about men in history who’ve made transatlantic crossings and links their stories—albeit tenuously—with the personal stories of women who’ve played tangential roles in these events. The first part of the book takes history out of order: 1919, the first nonstop flight across the Atlantic Ocean by aviators Jack Alcock and Arthur Brown, Newfoundland to Ireland. (This was my favorite, but unfortunately, the shortest, at 31 pages.) 1845, freed slave and abolitionist Frederick Douglass, on a lecture tour for his autobiography in Ireland. 1998, Senator George Mitchell brokering peace talks in Northern Ireland. The women and their families, spanning five generations, provide the thread linking these events. The second part of the book takes these generations in chronological order, in four sections dated 1863-1889, 1929, 1978, and 2011.

On to TransAtlantic by Colum McCann. The construct of this novel is unique. McCann takes three fact-based story lines about men in history who’ve made transatlantic crossings and links their stories—albeit tenuously—with the personal stories of women who’ve played tangential roles in these events. The first part of the book takes history out of order: 1919, the first nonstop flight across the Atlantic Ocean by aviators Jack Alcock and Arthur Brown, Newfoundland to Ireland. (This was my favorite, but unfortunately, the shortest, at 31 pages.) 1845, freed slave and abolitionist Frederick Douglass, on a lecture tour for his autobiography in Ireland. 1998, Senator George Mitchell brokering peace talks in Northern Ireland. The women and their families, spanning five generations, provide the thread linking these events. The second part of the book takes these generations in chronological order, in four sections dated 1863-1889, 1929, 1978, and 2011.